Addressing criticisms targeted at a study showing GM maize harmed the health of rats, a campaigner concludes that the public was misled in order to protect powerful commercial interests.

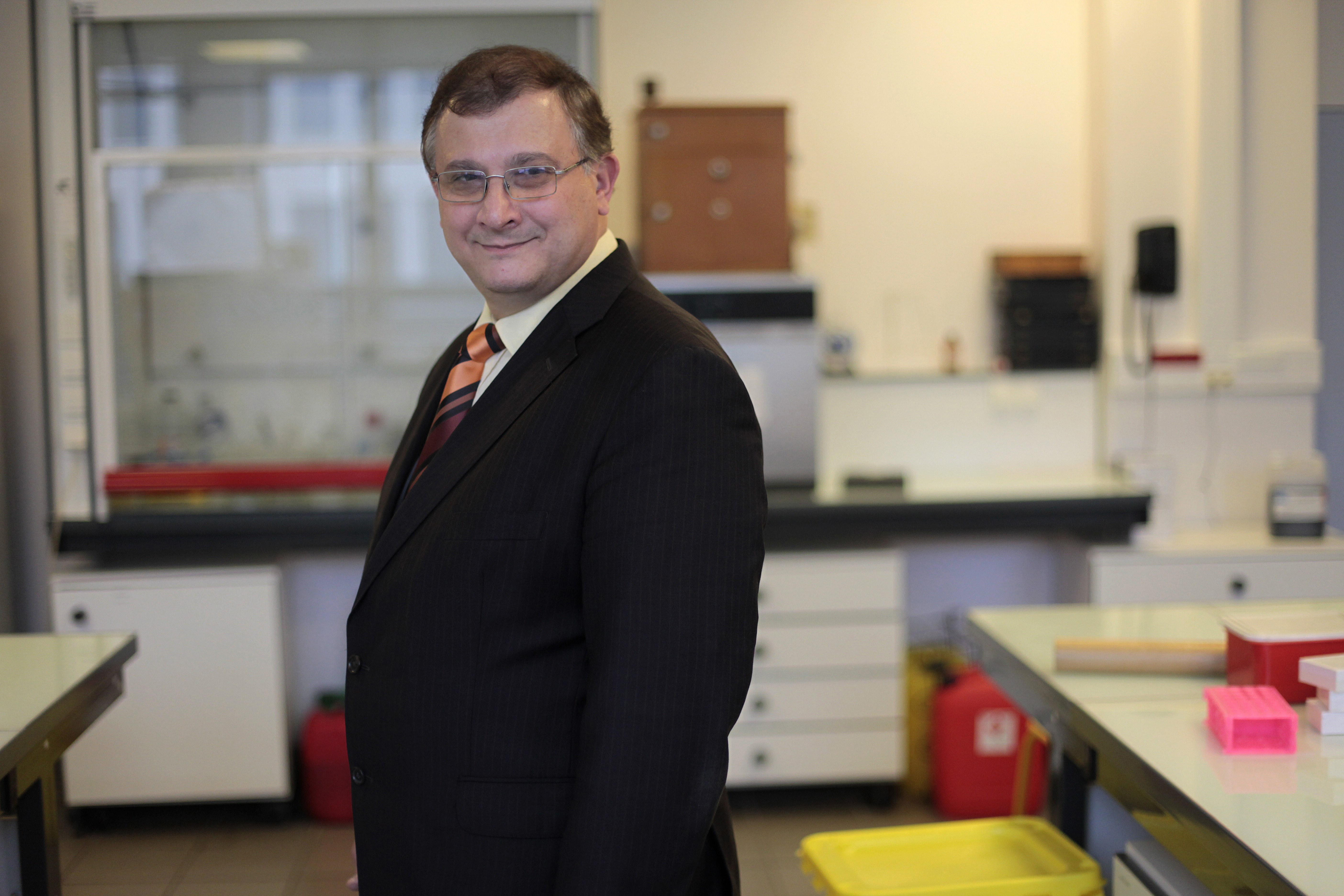

When a scientific study was published in September last year showing that a genetically modified maize and tiny amounts of the Roundup herbicide it is designed to be grown with damaged the health of rats, Corinne Lepage MEP called it “a bomb”. The study, by Prof Gilles-Eric Séralini’s team at the University of Caen, France, was the first to test the effects of eating a GM food and its associated pesticide over the animals’ lifetime of two years. The study found that GM maize and Roundup caused severe organ damage and increased tumour rates, as well as earlier death.

Lepage knew that if Seralini’s findings were taken seriously, the implications for GM firms and regulators were huge – GM foods are approved on the basis of rat feeding studies that last 90 days at most, equivalent to only seven to nine years in human terms. The tests are done by the same GM companies that want to market the GM seeds. The European Food Safety Authority has argued that even these short tests are not always needed.

Monsanto’s 90-day rat feeding study on this same GM maize had found differences in the GM-fed rats. But the EFSA claimed they were “of no biological significance” and agreed with Monsanto that the maize was as safe as non-GM maize. Séralini’s team obtained Monsanto’s raw data and re-analysed it. They found signs of liver and kidney toxicity in the GM-fed rats, publishing their findings in 2009.

Séralini carried out his recent study to follow up these initial findings of toxicity and to see if they were insignificant, as the EFSA claimed, or if they developed into serious disease. The findings were alarming. The initial signs of toxicity in Monsanto’s 90-day study developed into full-blown liver and kidney damage over the longer two-year period. The first tumours only showed up four to seven months into the study, peaking at 18 months.

The common sense conclusions were clear. The 90-day tests routinely done on GM foods are simply too short to see effects that take time to show up, such as organ damage and cancer. And regulatory agencies like the EFSA may be liable for allowing unsafe GM foods onto the market. But this common sense conclusion was not allowed to gain traction. Within hours of the study’s release, it was shouted down as flawed and meaningless by a chorus of scientist critics.

The criticisms were circulated to the press by the United Kingdom-based Science Media Centre and its sister organisations in other countries. Most of the world’s media took the criticisms at face value. The focus of the story shifted from the alarming health risks of a poorly tested GM food to “junk science” that should never have been published.

But all was not as it seemed. Many of the critics were subsequently exposed as having commercial or career interests in GM technology – interests that went undisclosed in media articles that quoted them. The Science Media Centre itself has taken funding from GM and agrochemical companies. Government agencies that condemned the study, such as the EFSA, had been involved in GM crop approvals and so were simply defending their own decisions.

The conflicts of interest would matter less if the criticisms had a solid scientific basis. But most were absurd. For example, critics said Séralini used a strain of rat prone to tumours. But Séralini used the same strain of rat that Monsanto used in its 90-day study on this GM maize and its two-year cancer studies on glyphosate, the chemical ingredient in Roundup herbicide. And research shows that this strain of rat is about as prone to tumours as you and I, making it an excellent human-equivalent cancer model.

Contrary to the critics’ message, the ‘scientific community’ has not united to condemn Séralini’s study. Many scientists, unconnected with Séralini’s group, are alarmed by what they see as suppression of scientific findings that are inconvenient to commercial or political interests. Some contacted me with their concerns and we joined forces to create a website, GMOSeralini.org, to offer the public and journalists a balanced view of Séralini’s findings and what they mean for our health.

None of the scientists claimed that Séralini’s study is perfect. All studies have flaws and limitations. But many said that this was the most detailed study that had ever been done on the health effects of a GM food that’s already in our food supply. The clear conclusion is that all GM crops and pesticide formulations must be tested in lifetime feeding studies to determine any health risks to humans.

Claire Robinson is managing editor of GMOSeralini, an editor at GMWatch and research director at EarthOpenSource.

Claire Robinson

Public Service Europe, 14 January 2013

Seralini = My Hero

It would seem that there are a lot of people who care more about their vested interests than the health and well-being of their fellow man. Selling this product to trusting citizens is a crime to humanity. Anyone who has suffered the loss of a loved one to cancer, particularly at a young age, wants to avoid that same fate for their loved ones. Consumers have a fundamental right to protect their health and to know all the facts of what they are putting into their shopping basket. I commend Gilles-Eric Seralini for having the courage to do this GMO rat study. He has performed a true service for humanity.